***I originally wrote this post for the

Urban Yarns Blog on November 11, 2014. It is reproduced here with permission.

Hey everyone, today (actually there will probably be a few posts in this series) we are going to start talking about colour. Not colourwork exactly (which you may know is a favourite pastime of mine), but some basic colour theory that holds true for all your knitting, and quilting, and drawing, and painting, and crafting, and just generally experiencing the world through a critical lens.

Ok, maybe you don't want to experience the world through a critical lens, so let's just say that this discussion might help you pick out yarns in the future. Good enough? Great, let's begin.

Our perception of a colour has three main elements: Hue, Value, and Saturation. Hue is what most people think of when they refer to a colour. Often represented on a colour wheel, most people know the primary colours* (red, blue, yellow), and secondary colours (green, purple, orange).

Hue is what we obsess over when we ogle

Madelinetosh or

Sweet Georgia. We will talk more about hue later, and its importance in yarn selection.

(Yes, I know that there are eight colours on that wheel, not the six I mentioned)

Saturation is related to the perceived intensity of a colour. You can add (imagine actually mixing paints on a palette) white to a colour to make a lighter tint, or grey to a colour to make a muddier tone, or black to a colour to make a darker shade.

But today I want to focus on Value. Value refers to how light or dark colours are in relation to each other (or rather, to a grayscale that ranges from pure black to pure white). Value is really critical to colourwork, as yarns with a similar value are harder to tell apart than yarns with very different values - regardless of their hue! In fact I would go so far as to say that value is the number of determiner of effective colourwork (bear in mind, I could choose some dreadful combination of hues, but still have an effective design).

(A monochromatic grayscale, from white to black)

Put bluntly, if you are working on a colourwork design (hey, ask one of our amazing staff nicely, and they will help you pick a great pattern...) that is worked in two colours, you want them to be of substantially different values. If you are working with three colours, you probably want them to be substantially different in terms of value. But as you add more colours, it does get trickier - er, this is also a discussion for later.

So, how do you apply this theory of colour value to your yarn selection? The technical term is "value testing", which really just means using method to assess whether or not your chosen colours are too close in value. Again, I hear you cry, 'how?'

Well the tried and true method is to squint. Simply put your yarns down on the table (ideally in good, natural lighting), and mush them up nice and close to each other, and squint. If, the more you squint, the more similar the value of the yarns seem to be be, then they probably are similar in value. If you can still easily distinguish between the yarns, you are likely on the right track.

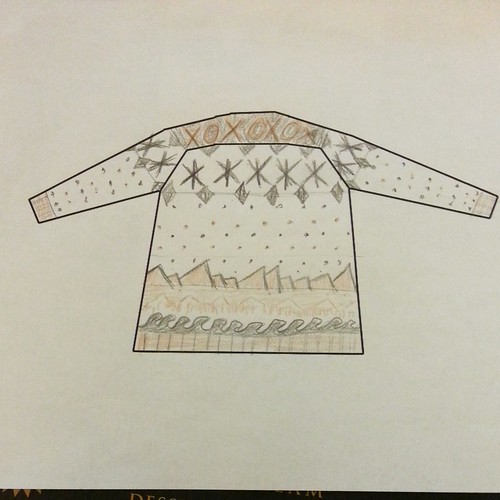

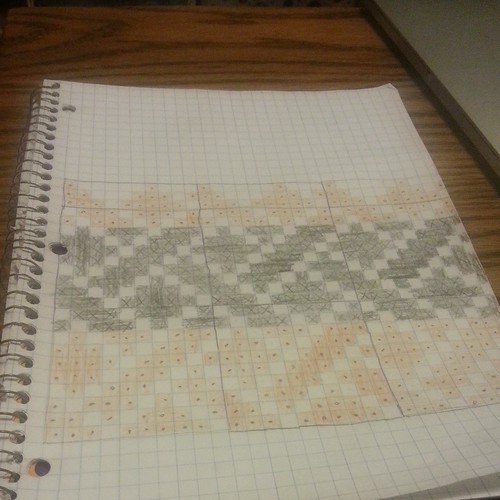

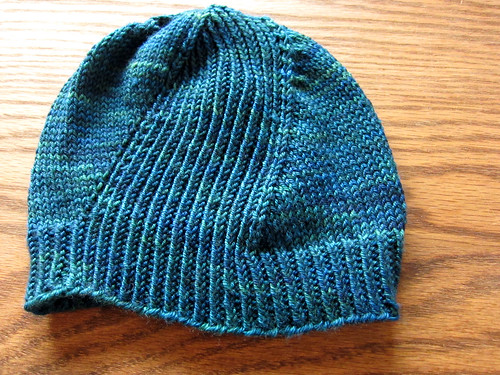

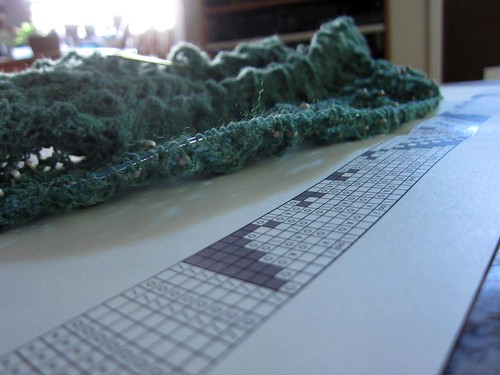

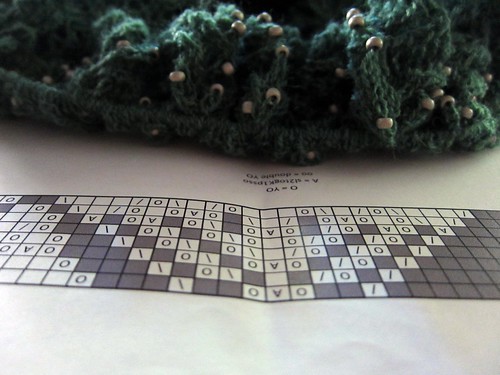

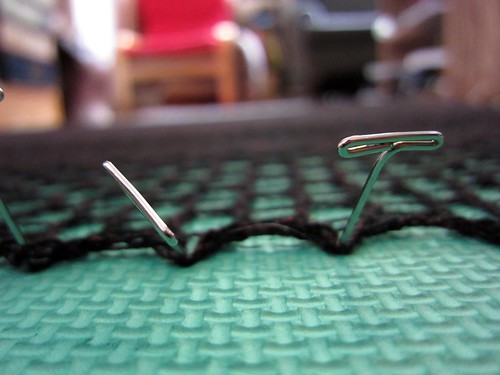

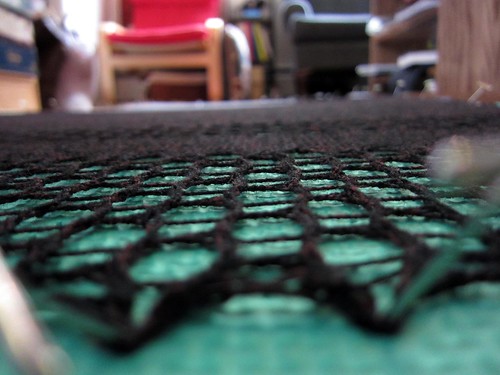

If you don't feel like squinting in the yarn store, we thankfully have technology at our disposal. With a camera or smartphone, take a photo of the yarns in question, and convert it to black and white. Really, it's that simple. This conversion will make abundantly clear just how close in value your yarns are. To illustrate, here are two simple projects I knit.

The first has a high value contrast between the red and yellow yarns, as you can see in both the colour and black and white versions.

The second photo... not so much.

In the black and white version it is almost impossible to tell the two yarns apart. Which is more effective?

As a parting thought, I've applied the same treatment to the

Rowan Pure Wool Worsted shadecard, and it's pretty interesting to see exactly what the range of values is (one of our hands down favourite yarns for its knitting properties and the fact that it comes in 56 colours...)

Anyway, I hope you've found this as interesting as I have, and would love to know what technique tips and tricks you would like to learn more about in the future! Drop us a line and let me know...

*Fun side note, the history and debate about the language of colour is a fascinating study. If you are linguistically inclined, I highly recommend reading into the

universalist/relativist debate.